- Home

- Lynch, R J

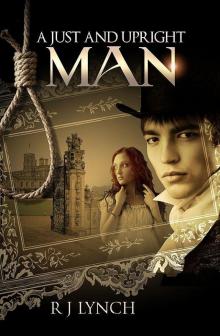

A Just and Upright Man (The James Blakiston Series) Page 3

A Just and Upright Man (The James Blakiston Series) Read online

Page 3

‘He might have been a miser.’

The curate shrugged. ‘I saw no sign of it,’ he said again. ‘And those scratches you speak of were caused by a bill hook or something of the sort. Someone has tried to remove the stone there, and if you will listen to a mere curate I shall tell you why.’

Blakiston struggled to keep the smile from his lips, but failed. ‘Please, Mister Wale. Tell me.’

‘If the money was not in his chest, it was hidden in the fabric of the wall itself. That is what foolish people believed. Someone has opened the chest, and when they found nothing they have searched for the supposed cavity in the wall.’ The curate’s voice rose an almost feminine octave, as though frustrated by the stupidity of the flock the Almighty had assigned to him. ‘The merest dolt could see there is not sufficient thickness for a hiding place, but greed turns men’s minds to butter. And he said unto them, Take heed, and beware of covetousness: for a man’s life consisteth not in the abundance of the things which he possesseth.’

‘Then who did this thing? Who killed the old man for money he did not have?’

‘I do not know. But there was a man. I thought him a vagrant. He was here, in the parish, the day Cooper died.’

‘Why did you think him a vagrant?’

‘He was in rags; he looked half starved; I had never seen him before.’

‘How fortunate for this penniless mendicant to find himself in the company of a Christian gentleman like you. You took him home, fed him, gave him a new suit of clothes and sent him on his way praising the Lord?’

‘I told him to get out of the parish by the shortest possible route. But first I demanded he tell me his name, and in what parish he was settled.’

‘Your charity does you great honour. And what was his name, and where was he from?’

‘He attacked me with a stick.’

‘To treat with violence a reverend gentleman intent only on his salvation. Shameful. So you did not get his name, or his home parish?’

‘I did. I wrenched the stick from him and beat him about the head.’

‘So his name was...?’

‘Joseph Kelly.’

‘An Irishman.’

‘His father may have been. This man said he came from Hornsea, which by his accent I could believe.’

‘I do not know the place. Did he then leave?’

‘He refused to do so. He said he was not a vagrant. He said he had three pounds on his person, which he showed me, and must therefore be left free to complete his journey, and that he was on his way to visit an old friend. I asked who and he said I had no right to know. I asked why he was walking so far instead of riding or travelling by coach. He said time was not a trouble to him. I told him to be off.’

‘Which way did he go?’

‘I met him in Swalwell. He took the road for Winlaton. I did not see him again. But if he followed that road, it would have brought him at last to Ryton.’

‘And you think this Joseph Kelly was the killer of Reuben Cooper?’

‘He may have been; he may not. One man was killed, and another was on our roads who should not have been. How could I know whether he killed the old man? To say that I should have had to see the murder take place and I did not. I have drawn your attention to his existence. That is all.’

‘Well, it is something. I shall have to see whether anyone else met this man. Was anyone about at the time you saw him?’

‘I recall no-one.’

Blakiston considered the curate for a few moments. Then he said, ‘What was the substance of your argument with Cooper on Saturday last?’

Wale’s eyes widened. ‘I have said nothing of any argument.’

‘You have not. But one of Cooper’s neighbours heard raised voices from this cottage and one of them was yours.’

‘Deliver my soul, oh Lord, from lying lips, and from a deceitful tongue.’

‘But why should they lie about such a thing?’

‘This is a rebellious people, lying children, children that will not hear the law of the Lord.’

‘Did you know Cooper before you came to this parish?’

‘By what right do you question me?’

‘Did you know him?’

‘I did not.’

When Blakiston dismissed him, Martin Wale mounted the poor nag that would carry him home to the mill in Winlaton. Nerves strained by a celibacy that had lasted too long, he yearned for something else before he took to his narrow bed beneath the miller’s roof. What he wanted was wrong. It had already caused more trouble than he would have believed possible, and it carried the threat of an eternity burning in hell instead of singing the praises of his Lord in heaven as he, possibly alone in the whole of Ryton, deserved.

There was no need to decide now. He did not have to commit himself just for the moment. If he headed his horse in the direction of Mary Stone’s hovel, that did not mean he had to enter when he reached it. And if he did enter, that did not mean he was certain to soil his purity with the jezebel once more. He did not have to writhe all night in shame and fury at his own weakness, or in terror that his life might end before he had time to make things right with God. In the grip of Asmodeus, demon of lust, he might call on that devil’s personal adversary, St John, to help him. He might enter Mary’s poor home only to kneel with her and pray.

It did no harm to let his horse go in that direction at the very least. And, in all conscience, the animal knew the way.

Chapter 6

After his conversation with Wale, Blakiston called on the Rector. ‘Your curate is a strange man for a servant of God.’

Rector Claverley smiled. ‘There are many ways to God. Poor Martin knows only one. He shall drink the wine of God’s anger which stands ready, undiluted, in the cup of His fury, and he shall be tormented with fire and sulphur in the presence of the holy angels. The tormented soul being mine, with Martin as one of the angels. My curate prefers the judgements of the Old Testament to the forgiveness of the New. He is unassailed by doubt. Martin knows that he is right and all who disagree are wrong. And yet he is but a curate and will never be otherwise, for he has no connection to find him a better place. Martin is a bitter man, Mister Blakiston, and he allows people to see his bitterness.’

‘Will he not receive his reward in the life to come?’

‘Blakiston, a vindictive person would whisper in the ear of Lord Ravenshead that you do not always seem firm in your devotion to our Lord. A vindictive person might even suggest that you were not merely a dissenter but an atheistical free-thinker of a sort his Lordship might not wish to employ as his agent. I am not a vindictive person, Blakiston, but I hope you have not expressed yourself with such levity in my curate’s presence. Will you take a glass of wine with me?’

‘I will with pleasure. And you may tell me of Reuben Cooper’s children.’

There was a knock on the door, followed immediately by the entrance of a woman almost as tall as Blakiston whose eyes and mouth suggested an amused delight in life.

‘Blakiston,’ said the Rector. ‘I do not believe you have met my wife.’

Blakiston stood and bowed. ‘Lady Isabella,’ he said, taking the offered hand, ‘it is a pleasure to meet you.’

‘My husband has told me much about you, Mister Blakiston,’ said Isabella, ‘but I fear he has forgotten his own bachelor days.’

‘Whatever can you mean, my dear?’ asked Claverley, but Isabella ignored him.

‘Before Thomas allowed himself to be domesticated, he relied on his married acquaintance to provide him with good food and company. One might expect him to be easy now in offering the same comforts to others, but it seems not. And so it falls to me to do what my neglectful husband should have done and to invite you to take dinner with us on Sunday evening. An invitation that I hope will

be repeated each following Sunday, until that happy day when you enter the married estate.’

‘Then I fear I may be your delighted guest for many years to come, Lady Isabella. But I thank you for your kind invitation.’

‘Thanking is not enough, sir. You must also say you accept.’

‘With all my heart.’

‘Rosina will be delighted. She finds it tedious to cook only for the two of us. A robust new appetite will please her greatly. And on Sunday she will be doubly pleased, for I shall invite other guests to meet you. I leave you to your talk, gentlemen.’

That night, when Claverley had finished disrobing in his dressing room, Lady Isabella was in bed waiting for him.

‘What did the pair of you talk about this morning?’

‘Many things,’ he said. ‘But mostly he wanted to know about Reuben Cooper’s children. Who they are. What they do. Where they may be found. How they felt about their father.’

‘Why on earth did he want to know all that?’

‘He wishes to establish how the old man died. If he was killed, the family of such a monstrous curmudgeon must fall under suspicion.’

Isabella’s hand covered her mouth. ‘Killed? You mean he did not simply die in the fire?’

‘I mean that we have not ruled out the possibility, my dear.’ He prepared to blow out the candle.

‘Sir Thomas,’ whispered Isabella. ‘Must we be in the dark so soon? Is there no way I can hold your attention a little longer?’

‘Oh. Oh, I see.’ He rolled over and kissed her on the lips. ‘My dear.’

She giggled. ‘But, please, my love. Take off that ridiculous nightshirt.’

Later, as they lay wrapped around each other on their soft mattress, Isabella said, ‘What do you make of him?’

‘Him?’

‘Mister Blakiston. Of whom else were we speaking?’

‘Oh. Blakiston. He is a good man and he will be a good friend. A little blunt, you know, but a man’s all the better for that.’

‘Yes, yes, very well, but the mystery surrounding him? What of that?’

‘Mystery? What are you talking about, Isabella? He is a land agent.’

‘My dear husband, do you see only the bluff exterior? The man possesses a desperate sadness. And in one so young. He cannot be more than twenty-five, would you not say?’

‘I believe he is but twenty-three.’

‘And he is haunted. You must see it. Surely?’

‘Ridiculous. You have been reading too many novels.’

‘I do not read novels. As you know. Really, Thomas. How can you possibly be a shepherd to your flock when you simply cannot tell what a man has in him?’

‘But...’

‘Why has he never married? An attractive man like that, why has he no wife? Well, perhaps he is too young, but why is he not at the very least affianced? Why is there no feminine connection?’

‘He never met...ah.’

‘You see? There is something.’

‘I believe we should respect his privacy, my dear. He did say there was once a woman he expected to marry.’

‘Yes? And?’

‘And what?’

‘Did she die? Did he desert her? Did she abandon him? Is she married to another? Incarcerated in a home for the infirm of mind? Has some evil relative with eyes on her inheritance locked her in an attic? What happened?’

‘Isabella, I really have no idea.’

‘Oh! For goodness sake. Why do men never ask the right questions? Blow out the candle.’

Blakiston stood in the dark looking out of his window onto the silent, deserted road outside and thinking about the day. The dreadful sight and smell of Reuben Cooper’s burnt body. The strange interview with Martin Wale. Claverley’s account of so many children, all to be investigated if the death turned out not to be the work of malign fate. A man wandering the roads, who might be Irish or might not, and might be a killer or might not, but who at any rate must be found and questioned. The looming shadow of enclosures. A drunken farmer and an idle one, both to lose their livelihoods if he had anything to do with it.

And, underlying all, the painful recollections that never quite went away, of the woman he had expected to marry and the hurt of his loss. He would never allow himself to love again. Of that he was certain.

Lizzie Greener, too, stared into the dark. The raw fury had not abated. Everyone around her talked about the death of Reuben Cooper, and whether it was murder, and no-one spoke of what had been done to her. But when she closed her eyes, when she saw above her the face of the Earl as he took her with not a care for the human being beneath him, when she remembered the sovereign tossed with casual disdain on the ground beside her…when she thought of these things, Lizzie understood that murder was possible. She knew how someone might be led, by rage and the desperate need for revenge, to end the life of another human being.

She had stared into the eyes of her despoiler as he had risen from her, and he had looked away, unable to hold her gaze. She had seen it for only a moment, but it had been there. And then the Earl had shrugged—physically shrugged—as though shaking off a feeling he could not bring himself to entertain. But, somewhere beneath that carapace of luxury and power, was a man capable of shame.

She hoped that shame would follow him to the grave.

And, under all this, Lizzie had her own feelings of guilt. For people wished to know what had happened to Reuben Cooper, and Lizzie was sure that she knew, and she had told no-one. Reuben Cooper was a vile man who more than once had made disgusting advances to her and he had been killed for it.

But Lizzie would keep the killer’s identity secret.

Chapter 7

It was simply the most modern and comfortable house Kate had ever been in. She knew Mistress Wortley to be a widow, and in Kate’s experience widows were always in want of money. There was no sign of that here.

Though the hovels of the poor—hovels like the one Kate lived in—had no floor coverings at all, she was familiar with the floor cloths better off people had. Sheets of canvas drenched in linseed oil and pigment, they gave some pattern and colour but, most of all, they kept the feet clear of the cold stone flags or beaten earth that constituted the floor of most houses. Here, though, were no floor cloths. This floor was smooth-surfaced terracotta tiles, swept clean by one of the three servants who looked after this one woman’s every need; and on the tiles lay rugs of woven wool in intricate and brightly coloured designs. Kate stared in wonder.

‘I see you are looking at my rugs, Katherine. You are perhaps wondering why they are not on the wall, as you might have seen in, let us say, the Rectory?’

Kate nodded, though in truth she had never been further into the Rectory than the scullery, and the only hangings there were copper pots and pans.

‘This is the latest fashion, Katherine. Everyone in London is doing it. Hangings are coming off walls and going onto floors. And, see: the blue and yellow wallpaper. I had it delivered by James Wheeley in London. They sent their own men all this way to hang it, for I could not trust the local workmen. It is the newest thing. Would you really cover such a bright and beautiful paper in wall hangings?’

Kate was almost lost for words at such elegance. ‘No, miss.’

‘The people of Ryton do not know what beauty can exist in our world. Beauty is to be found only in Mayfair. And, of course, Paris, Rome, Venice.’

‘Lady Isabella goes every summer to Harrogate. We pray in church for her safe return.’

‘Yes, I can see that a provincial soul might warm to Harrogate. For me, Bath is not entirely without its compensations. And now, tell me. Why do you want to learn to read and write?’

‘Miss, I want to better myself. I want to read the bible for myself, instead of hearing only what someone else

thinks is important. And I’d like to know what’s going on in the world.’

‘Very well. Estimable wishes, so long as you do not think to rise above your station. But reading and writing are not enough. You must also learn to speak.’

‘Speak, Miss? But, Miss, I speak every day. I am speaking to you now.’

‘That is not speaking. You have much to learn. For now, let us content ourselves with but a few simple rules. You must not say us when you mean me. You must not say our Mam, but my mother. Or, better still, simply Mother. You will not call people Man, whatever sex they may be. And never, ever, shall you address someone as pet. Is that clear? There will be more to learn, when you have mastered this. I shall call you Katherine. You will call me Mistress Wortley, or Ma’am. And now, let us begin. But what is that?’

‘Mistress Wortley, it is a penny. I wish I had more, but...’

‘Put it away. Do you imagine I am some schoolmistress or governess, available for hire?’

‘But...’

‘I do not need your money, child.’

‘But...’

‘Katherine. You have explained as well as you can why it is you wish to read and write. Let me offer another explanation, which may be closer to the truth. Somewhere in your rustic Ryton head is the faint and misty realisation that the world you know is not the only world there is. That there are other worlds, and that you would like to know what some of them are like, and how people live there. Is that not correct?’

‘I...I suppose so, Miss. I mean, Mistress Wortley.’

‘Well, Katherine, you may start here. Yes, I am a widow. But I am not like the widows you know. I am the widow of a successful lawyer, Katherine. He was sixteen years my senior, and he had the grace to die when he was only forty-six. He left me at thirty after four years of marriage with no children and enough money to live as I wish.’

A Just and Upright Man (The James Blakiston Series)

A Just and Upright Man (The James Blakiston Series)