- Home

- Lynch, R J

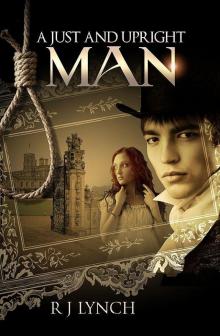

A Just and Upright Man (The James Blakiston Series) Page 2

A Just and Upright Man (The James Blakiston Series) Read online

Page 2

‘Had Cooper a chair?’

‘I was never in this house before, but it seems unlikely. His would be the only cottage in the village with such a thing, if so. Why do you ask?’

Blakiston pointed at the thick carpet of ash in which the body seemed to lie. ‘That looks to me like wood ash.’

‘A chair would lend credence to the idea that he had money. Chairs are expensive. Most of our people make do with settles against the walls, or stools. My curate would know.’

‘I shall ask him. I should like his view, too, on the appearance of this wall before the fire came.’ He pointed at the stones at the base of the wall, behind the burned corpse.

‘You are looking at those scratches?’

‘They could be new. Would you not say so? The flames and soot have darkened them, but I believe they may be fresh. I should like to know what was here. But now I must get away from these ashes before my feet roast. I think we must allow the men the same relief. And I have an appointment at eleven with Lord Ravenshead. Rector, we shall meet again later.’

When Blakiston had gone, one of the men approached the Rector and placed a twisted mass of singed wood at his feet.

‘What is this?’ asked Thomas.

‘Sir, I think it was a bucket.’

‘A wooden bucket? How did it survive the fire?’

‘Sir, I think it must have had water in it. And then, you know, when we threw water to put the fire out...’

‘Yes, yes. No doubt you are right. But why bring it to me?’ He peered into the bottom of the bucket when the man pointed. ‘Yes? What are you showing me?’

‘Sir, that looks like blood.’

‘Blood? Whatever makes you think that? All I can see is a sticky mess in the bottom.’

‘Well, sir, if you think it is nothing...’

‘No, no. I cannot say that. Put it in the church porch. I will have someone look at it.’

‘Yes, sir.’

Chapter 4

From Ryton, where he lived alone in a small, square house on the green opposite the church and the Rectory, the ride to Ravenshead Castle through the wild whinscapes of County Durham took Blakiston most of an hour. Before long, spring would bring the simple pleasure of watching fledglings learning to fly the nest. Not all would live to raise their own young in their turn. For bird as well as for man, life was precarious. Only the tough and the lucky survived.

Even in this frozen landscape, there was no shortage of life. The lonely cry of the curlew, the emblematic bird of this country, made him shiver. The sudden sharp bark of an over-wintering pheasant warned of the hawk circling above. As he climbed the gentle slope towards the castle, a red fox emerged through a hedge, paused to stare at him with its passionless eyes, and moved without haste across the field.

Every time he came here, Blakiston was face to face with the differences between the South he had known as a boy and the Northern counties he now called home. The mediaeval fortifications of Ravenshead spoke of a time, less than a hundred years ago, when Scottish invaders still brought murder and mayhem with them. Sussex by then had already known three hundred years of peace.

He gave his horse into the care of one of the stable boys and stopped in the kitchen to check his appearance in the glass. Then he made his way along stone-floored passageways till he came to the family’s quarters. Up a carpeted staircase, to enter Lord Ravenshead’s Business Office at five minutes to eleven. Two minutes later maids, supervised by the butler, brought in trays of coffee, tea, sugar and Scottish shortbread sweetened with caraways and orange peel. On the stroke of the hour, His Lordship entered through the door that led from his dressing room.

‘Blakiston! You look well.’ He advanced across the room, a tall broad-shouldered man, and shook Blakiston’s hand.

‘Thank you, My Lord.’

Ravenshead gestured towards the trays.

‘Allow me, My Lord. I shall take coffee. And you...?’

‘The same. And then you may tell me whether you believe I would be wise if I decide to extend the Estate.’

‘You have a farm in view?’

‘Three, in fact. The Bishop of Durham wishes to buy more land adjacent to some he already owns. To raise money for the purchase, he proposes to sell me three farms between here and Winlaton. I should like you to take a look at them, and tell me what you think of the tenants, and whether you could make something of them.’

‘The Bishop is a good landlord.’

‘The Bishop is a bad landlord, Blakiston, in that he cares nought for his tenantry. But he is bent on extracting the last penny from his lands, and he knows that modern farming methods will help him do that, and he has the wit to see that allowing them to keep some of the surplus encourages farmers to do what he wants of them. I would Sir Edward Blackett were of the same mind.’

‘I shall look this afternoon.’

‘The drawings are here. Take them before you leave. And now, tell me. What do you know of enclosures?’

‘My Lord, in Sussex all the land is enclosed. There are no common lands left.’

‘And have the enclosures been successful?’

‘For the landowners and the larger farmers, My Lord, yes. For the ordinary people, enclosure has been disastrous. They have been ruined. Cast out to make their living where and how they might.’

‘I have heard much the same. Well, we may see how it shall be here, for the Bishop and Sir Edward Blackett are keen to enclose the common lands and we may not be able to avoid it. But we shall talk more on that subject if it should come to a Bill. There was a fire last night in Ryton?’

‘Reuben Cooper’s cottage, my Lord.’

‘A most disagreeable man. He lost his life?’

‘My Lord, there is evidence that it was taken from him.’

‘What? You mean he was murdered?’

‘The Rector and I think it possible. There was a hole in his skull. It could have been made by masonry falling in the fire, but there is but the one hole, and that in the back of his head where a cowardly attacker might strike. My Lord, the death may have been entirely accidental. But, if it was not, I should like to search for the killer. My duty to you comes first, of course. It may take me some time to bring the murderer to book.’ He spread his hands. ‘In truth, I may never achieve it. But I should like to try.’

Lord Ravenshead nodded. ‘And so you should, Blakiston. Cooper was an insolent rascal and godless, but if he was killed then justice should be done. Perhaps the killer is here, a worker on my estate. Tell me what you have learned so far.’

‘I have not even begun. I wish to speak to the curate, who may be able to tell me something about the inside of the house, and then I must learn what enemies Cooper might have made in his life. A man is not battered to death for no reason.’

‘A list of Cooper’s enemies would make a large book.’

‘There is also the question of the treasure some in the village believed Cooper to have.’

‘Well, Blakiston, you will have your hands full. But, as you say, the Estate’s affairs must have first call on your time. Be a good fellow and run an eye over these farms before you begin looking into Cooper’s death.’

Wrapped warmly in his broadcloth coat and hat, pistols ready in case of footpads, Blakiston enjoyed the ride from Ravenshead Castle back to Winlaton, a landscape of low hills and farmland.

Early on a Wednesday afternoon in February, he would have expected to find farmers at work in cleaning, maintaining hedges and preparing equipment ready for the ploughing and sowing that would soon begin. This was indeed the case at the third farm, but he found the first farmer insensibly drunk and the second idle and insolent. The land, though, seemed good and the buildings could be brought into repair. Since all three farms together amounted to no more than three hundred and

fifty acres, Blakiston resolved to recommend to his Lordship that he complete the purchase, join the farms into one, place all under the stewardship of the third farmer and invite the other two to seek their living elsewhere. Larger farms were in any case more efficient than smaller, and you could not be offhand with Blakiston without expecting repercussions.

While Blakiston was deciding the fate of the three farmers, Kate Greener visited the church. She was not an uncommon visitor there; nevertheless, the Rector’s wife thought it worth mentioning in the journal she wrote each evening when dinner had been eaten, the baby was asleep and there were no other calls on her time. Other women of her class sewed, made decorative articles or played the piano. Lady Isabella recorded the doings of Ryton parish.

Wednesday, 2nd February, 1763

Poor Reuben Cooper died last night in a fire. He had probably gone to sleep with his pipe alight. I worry so often that Thomas will do the same in his study and burn us all to a crisp. Reuben was an unlikable man and I confess I find it difficult to mourn his passing; still, one of God’s creatures is gone.

Something interesting happened just after lunch today. Mistress Wortley had been at the Rectory to discuss what is to be done about the poor, or so she said; it became clear very quickly that she had news she thought I would find unpleasant and was in haste to pass it on. She knows that Mary Stone is a particular anxiety of mine, and that I spend time praying with her and talking to her. What she wanted to tell me is that Mary is still a harlot. Really, how did she imagine I believed poor Mary clothed herself and fed her children? She gleaned this information from her lady’s maid, who had it from their manservant, and how he gained it (and under what circumstances he passed it on to the maid) I should prefer not to enquire.

But that was not the something interesting. Mistress Wortley had arrived dressed in a manner no doubt meant to overawe a country Rector’s wife, and she treated me with her usual condescension, but there are deep pools of good in her. For when I walked her out of the Rectory, as she clearly expected me to do, we looked into the church, and Kate Greener was there, and—and this is the something interesting—Kate had her nose so deep in a Book of Common Prayer that she did not even hear us enter. Mistress Wortley whispered to me, “Is she not quite the most beautiful young woman you might meet in a hundred miles?” and of course she is. But it is not only appearance with Kate Greener, for she is also a good person. She smiles when she is happy, and when she sees something good happen to another, and not (as so many do) when they see someone discomforted. If she is asked to do something, she does it with a glad heart. And so I was pleased by what happened next.

“My dear,” said Mistress Wortley in a loud voice. Poor Kate was so surprised she leapt a foot into the air and rushed to close the prayer book and to move away from it. “When did you learn to read?” Mistress Wortley went on, walking towards Kate as she spoke. “Who taught you?”

Kate dropped a polite curtsey. “Ma’am, I cannot read,” she said.

“But I saw you!”

“I was trying,” said Kate.

“Trying? You were trying to read?”

“Yes, Ma’am.”

“My dear, you cannot try to read.”

I felt so proud of Kate then, for she stood her ground, embarrassed though she was. “Ma’am,” she said. “I thought that I had heard everything in this book read so often I might recognise the words. But it is hopeless. I cannot do it.”

“You would like to be able to read?”

“Oh, yes, Ma’am. More than anything in the world.”

“More than anything. More even than to find some well off farmer and become his wife?”

I have to say that Kate looked very thoughtful at that, for a well off farmer must seem an impossible prize for one as poor as the Greeners, and she did not answer. Instead, she said, “I should so much like to be able to read.”

“Then you shall,” said Mistress Wortley. “For I shall teach you myself. We shall start tomorrow. You know where I live?”

I could see that Kate was overwhelmed. “But...”

“I shall hear no buts. Do you know where I live?”

“Yes, Ma’am.”

“Then be there tomorrow at ten in the morning and we shall start work. An intelligent girl like you will be reading in no time.” She turned on her heel and walked out of the church with me following. “Till tomorrow.”

When we were outside she placed a hand on my wrist and said, “You will think me a fearful simpleton for what I have just done.” Of course, I entertain no such thoughts and would not have said so if I did. “It is the duty of each of us to do what we can to improve the situation of another of our sex. That young woman promises much, and I shall help her achieve it.” Then, with another patronising nod in my direction, she took her seat in her carriage and was driven away.

Chapter 5

Ryton was a huge parish and Martin Wale had been at the other end of it when word came that His Lordship’s overseer wished to speak to him. It was not till next morning that Blakiston was able to ask his view of the marks on the wall of Reuben Cooper’s cottage. By that time, Blakiston had talked to Cooper’s neighbour Dick Jackson and what he had heard had made him even more interested in what the curate should have to say.

What a curious sight Wale was. His britches too tight and too short as well as being, to Blakiston’s eye, too black. His hair unruly, his skin too unhealthily white, his jacket simply too old, his shirt creased and by no means clean. And his boots! Could the man not even polish his boots? As for his manner, Wale’s whole being radiated indecision.

Blakiston sighed. ‘I believe, Martin, that you wish to divine what I would like you to say, so that you can say it.’

The curate’s head bobbed.

‘It is a useless task,’ said Blakiston, ‘for I do not know myself what I would like you to say. Or, rather, I would like you to tell me the truth to the very best of your ability. That is fitting to your priestly calling, is it not?’

‘Mister Blakiston,’ said the curate in his pinched, nasal voice, ‘I do not think you should speak to me in that way, and nor do I believe that you should be so easy with the duties of a priest.’ Small, bloodshot eyes turned to look at Blakiston. ‘We hear the rumours about your free thinking and lack of faith. I may be only a curate, but...’

‘Excellent, excellent,’ cut in Blakiston. ‘I have made you angry, and now you may begin to act like a man and so we may get somewhere. Turn your mind away from the inside of mine, which surely is no business of yours, and look at those scratches. It is a simple question. Were they there when last you visited Reuben Cooper, or were they not?’

‘I have no way of knowing. The wall was obscured.’

‘Thank you. Though why you could not say that at the outset, I do not know. Seeking to please others is no way for an educated man to act.’

‘I seek to please only God,’ spat out the curate.

‘Then please Him still further by helping me learn how a poor old man died. When were you last in this cottage?’

‘Four days ago. I visited Reuben Cooper every month, on the last Saturday.’

‘Commendable. And was he pleased to see you?’

The curate looked away. ‘They are not Godly people here.’

‘I see. He did not want to see you, but still you persevered.’

‘Behold, I send you forth as sheep in the midst of wolves: be ye therefore wise as serpents, and harmless as doves.’

‘There are no wolves or serpents in Ryton. Unless you believe in the story of the Lambton worm, which frankly I do not.’

‘Whosoever shall not receive you, nor hear you, when ye depart thence, shake off the dust under your feet for a testimony against them. Verily I say unto you, It shall be more tolerable for Sodom and Gomorrah in the day of judgment, than fo

r that city.’

‘And blessed be the meek, for they shall inherit the world. Amen. I hope you do not have to wait too long for your inheritance.’

Wale’s eyes fixed unblinkingly on his, and it was Blakiston who looked away first. ‘What exactly was it that hid this wall four days ago?’

‘A wooden chest stood there.’

‘A chest! Did you ever see inside it?’

‘I did not. The old man used it as a seat.’

‘He never alluded to its contents?’

‘Not he. Others did.’

‘Others?’

‘This is a country parish, and a closed one. The people are suspicious of strangers. They are suspicious of me and they are suspicious of you. ‘

‘I have always found the people of Ryton to be open and friendly.’

‘You bring them work, or withhold it. You do not have to look daily into their black souls. You are not required to save them when they do not wish to be saved.’

‘Mister Wale, I believe it could be that they are open and friendly with me because I do not treat them as my foes. Be that as it may. Reuben Cooper’s chest.’

‘Cooper was an outsider. People had no handed down history of his father and his grandfather and his father before him, as they have of most of their neighbours. Having no knowledge, they invented. Cooper was a man of the sea, an alien place to them. They could as lief have decided he sprang from a union between Neptune and a mermaid; but what they settled on was that he had been a pirate and was rich.’

‘And kept his money in the chest.’

Wale nodded.

‘You think he was not a pirate?’

‘His first settlement was a bay to the north of Scarborough. A godless, lawless place. I make no doubt smuggling would not have troubled him when the opportunity came his way, but I am sure he was not rich. I saw no sign of it, at any rate.’

A Just and Upright Man (The James Blakiston Series)

A Just and Upright Man (The James Blakiston Series)